The book “Entrepreneurship and Management in an Islamic Context” is now available. I was asked to write the Foreword, which I am happy to share here:

I am honored and humbled to write this Foreword for a handbook that presents a comprehensive overview in an emerging area of research offering manifold insights for theory and practice. The oeuvre in front of you reaches across space from Ghana, Jordon, Lebanon to the UAE; across time from early Islam to the present; across categories such as ethnicity, gender, nationalities and age; and across topics from Islamic Entrepreneurship, Finance, Leadership to Management. It also tackles both text and context: from sacred scripture up to profane practice.

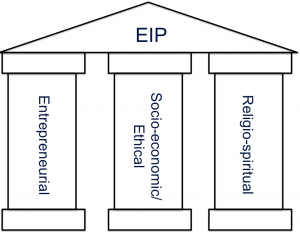

While religion matters in entrepreneurship and management practice, its theory and theorization is dominated by a sacralized secular hegemony. Yet, religion is a social fact that matters in and around organizations; and the social sciences explain – not prescribe – reality. Islam specifically is the second largest religion in the world with a growing number of adherents. Religion in general and Islam in particular thus warrants much more critical engagement and analysis through management scholars. Such scholarly pursuits connect work with worship to examine what I call ‘wor(k)ship’, whereby religious people wish to do well while adhering to their faith, rather than compartmentalizing their lives into different spheres.

While religion matters in entrepreneurship and management practice, its theory and theorization is dominated by a sacralized secular hegemony. Yet, religion is a social fact that matters in and around organizations; and the social sciences explain – not prescribe – reality. Islam specifically is the second largest religion in the world with a growing number of adherents. Religion in general and Islam in particular thus warrants much more critical engagement and analysis through management scholars. Such scholarly pursuits connect work with worship to examine what I call ‘wor(k)ship’, whereby religious people wish to do well while adhering to their faith, rather than compartmentalizing their lives into different spheres.

The false dichotomy between the public and private, the professional and the personal underlies a deep desire to structure and categorize, to identify and delineate boundaries in a complex modernity. These socially constructed boundaries enable and constrain us concurrently. They are double-edged swords. The predominant scholarly pursuit for parsimonious explanations as well as the increase of scholarly specialization has lead to jurisdictions within our very own professional communities and the partitioning of the objects of inquiry. This handbook, in contrast, offers an interdisciplinary approach that bridges rather than reinforces artificial boundaries.

Even more so, I believe that, unfortunately, the theoretical partitioning has permeated the very phenomena to an extent that theory does not simply explain, but rather forms reality. Academics may wish to restrain the world through theory and thus fall trap to the attempt to create a world according to their sometimes too simplistic imagination, rather than depicting the richness of reality. The handbook at hand offers a counterpoint. This may also help bridging what is sometimes called in the Christian faith the Sunday-Monday divide and whose equivalent may be the Friday-Saturday or Thursday-Friday divide for Muslims. The handbook thus offers practitioners a mirror to their religiously shaped intent, rather than to their learnt and potentially unintended practices.

I am grateful to the editors Veland Ramadani, Léo-Paul Dana, Shqipe Gërguri-Rashiti and Vanessa Ratten and the many contributors that they have taken upon themselves to push our knowledge frontier forward – in a realm that (still) faces many challenges. Religion is an integral part of our social and societal spheres, i.e., our soci(et)al context; yet largely absent from our literatures. This work is a significant step to counter that neglect by zooming in on the Islamic context. It remains for me to say to the reader that I wish this to be an illuminating, thought and practice challenging and changing read.

I have written an article for the forthcoming Special Issue of the Journal of Management Development. The overarching theme of the Special Issue is the Practical Wisdom for Management from the Islamic Tradition. In a former version of the article, I briefly compared my ethnographic experience in a Sufi Dhikr Circle, a mystical Islamic organization, with Wacquant’s experience as a participant-observer of boxing. This section did not make it into the final article. So here it is:

I have written an article for the forthcoming Special Issue of the Journal of Management Development. The overarching theme of the Special Issue is the Practical Wisdom for Management from the Islamic Tradition. In a former version of the article, I briefly compared my ethnographic experience in a Sufi Dhikr Circle, a mystical Islamic organization, with Wacquant’s experience as a participant-observer of boxing. This section did not make it into the final article. So here it is: